Cut the Technobabble

The marketing for Functional Programming is made of technobabble. Technobabble was used in Star Trek. Those long discussions are what Star Trek was loved for, but technobabble isn't good for sharing knowledge or advancing our field.

Technobabble: a type of nonsense that consists of buzzwords, esoteric language, or technical jargon.

This is a follow-up to my last article, “The case against Effect Systems (IO)”.

Composition #

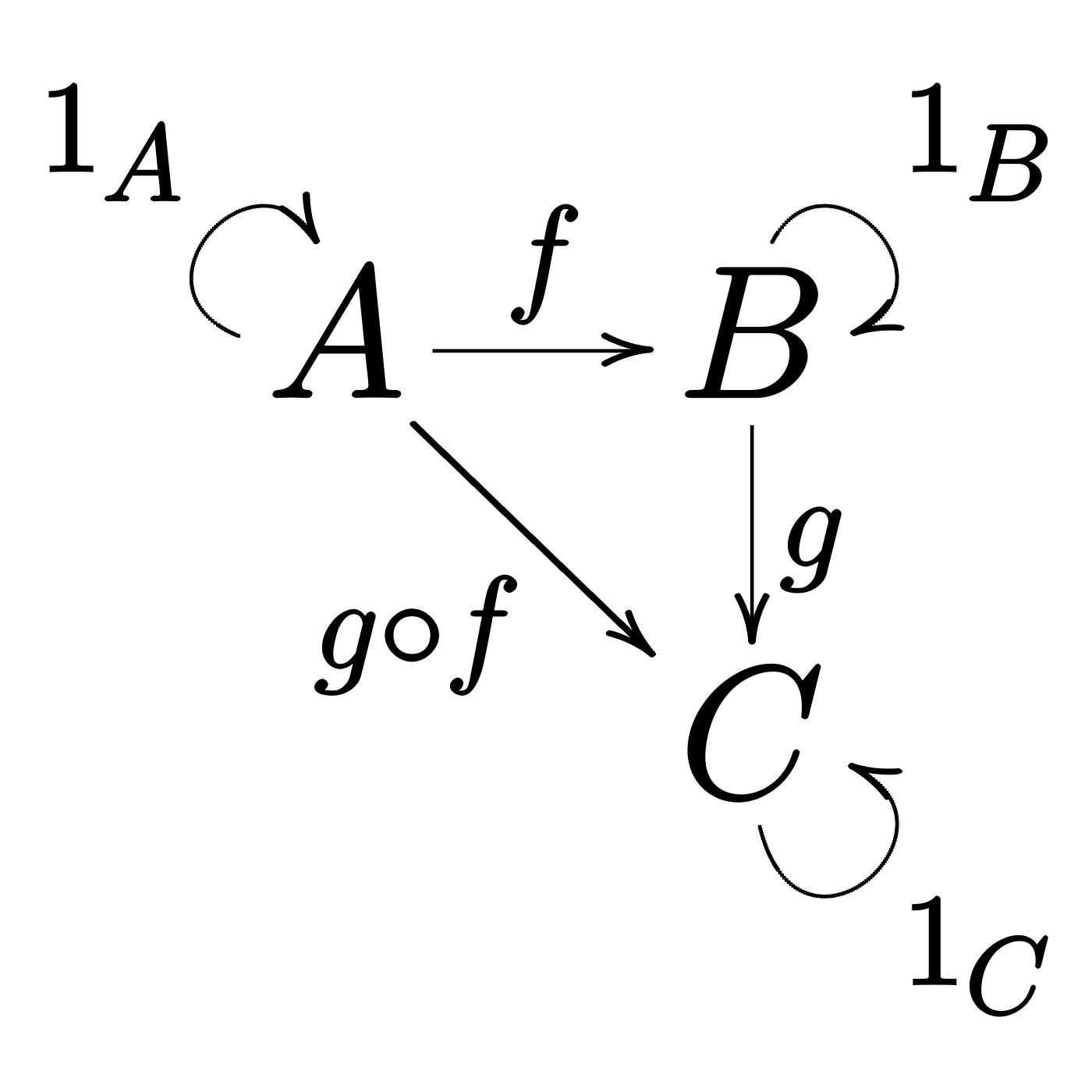

Composition is about taking pieces and combining them in a bigger piece. Functions are automatically composable, and in FP, when people talk about composition, they usually mean this:

It’s not just functions, that’s why we have “category theory”, but to put it plainly in code:

def functionAtoB: A => B = ???

def functionBtoC: B => C = ???

// We get this for free

def functionAtoC: A => C =

a => functionBtoC(functionAtoB(a))

This works if you have an F[_] monadic type as well, which is nice, and we can say that these functions provide us with a simple and established protocol to compose smaller pieces into bigger pieces:

def functionAtoB: A => F[B] = ???

def functionBtoC: B => F[C] = ???

// We get this for free

def functionAtoC[F[_]: Monad]: A => F[C] =

a => functionAtoB(a).flatMap(functionBtoC)

Different monadic types don’t compose well. So, for example, if you have 2 types, F[_] and G[_], you can’t automatically combine them into an F[G[_]] or G[F[_]] (think IO[Option[_]] and Option[IO[_]]). Knowledge of their monadic nature isn’t enough for you to do that, as you need more. Hence, we have a need for “monad transformers”, e.g. OptionT, EitherT, ReaderT. Or we need another type-class, like Traverse, which allows us to transform an F[G[_]] into G[F[_]] (e.g. (list: List[IO]).sequence). That, or you can basically take the monad transformers and combine everything into a bigger type. Obviously something like this can be hard-coded, to be more ergonomic and/or efficient, moving the costs around:

type ZIO[-Env, +Err, +R] = Kleisli[EitherT[IO, Err, ?], Env, R]

// type ZIO[-Env, +Err, +R] = Env => IO[Either[Err, R]]

But folks, from where I’m sitting, I don’t see that much automatic “composition” happening for monads, in general, compared to plain old functions. The “composition” happening in Haskell’s ecosystem, via the prevalence of monad transformers, is for me a turnoff, alongside ReaderT used for dependency injection, even when encoded into something more ergonomic. I’ll take Java’s Spring over that, thanks. But that’s just a personal opinion.

“Composition” is usually technobabble because …

Objects (from OOP) compose — that’s their whole purpose actually, that’s why we care about subtype polymorphism, or encapsulation, because it’s all about their composition. We may need design patterns to compose, but they compose well. And maybe we have a hard time coming up with an automatic protocol for it, i.e., drawing those arrows from category theory, but it’s composition nonetheless. And structured/imperative programming constructs also compose. It’s why you’re able to build anything at all.

In the context of IO, what people mean by “composition” is basically “reuse” via abstract interfaces (type classes). For example, it’s nice being able to transform a List[IO[A]] into an IO[List[A]], or a List[EitherT[IO, E, A]] into an EitherT[IO, E, List[A]], by using very generic functions that make use of type classes. For example, I love doing stuff like this:

// Scala code

def processInBatches[A, B](

batchSize: Int,

list: List[A],

job: A => IO[B]

): IO[List[B]] =

list

.sliding(batchSize, batchSize)

.map(batch => batch.map(job).parSequence)

.sequence

.map(_.flatten)

Functional programming is expression-oriented, we process stuff by transforming input into output via function composition, essentially assembling a pipeline. Working with IO here allows us to remain within this paradigm, and it’s awesome for it. Expressions are awesome.

But as far as composition is concerned, this argument isn’t as strong as you’d think, because in the context of blocking I/O and side-effecting functions, going from () => A to A or from List[() => A] to List[A] is trivial, not to mention you can always use plain-old foreach loops, which also compose 🤷♂️

I don’t see any monadic IO in the following code:

// Kotlin code — only used because Java currently needs boilerplate

suspend fun <A, B> processInBatches(

batchSize: Int,

list: List<A>,

job: suspend (A) -> B

): List<B> = coroutineScope {

list.windowed(size = batchSize, step = batchSize)

.map { batch ->

batch

.map { async { job(it) } }

.awaitAll()

}

.flatten()

}

And, say, if you want “compositional resource-safety”, nothing beats this in terms of how clear it is, or the contract that the JVM runtime gives you:

// Java code / try-with-resources

try (final var res1 = new Resource1()) {

try (final var res2 = new Resource2(res1)) {

//...

}

}

Cats-Effect’s Resource (or similar abstractions) is a super-power, being a presence in all of my Scala projects. However, it would be a mistake to think that more classic OOP alternatives aren’t available, or that it wouldn’t work with blocking I/O. The problem with resource management in Java is linked to bad design related to Closeable, or to the Java EE flavored dependency injection. C++ developers have a much better time with RAII, possibly because they have to do that for memory management, too, so it’s everywhere. I also find Scala’s own Using.Manager interesting, being a simple and effective way to cope with multiple Closeable resources in imperative code. And better options can happen for imperative code too. Solutions like Resource aren’t perfect either, because we can leak references, to be used after they are disposed.

In short: expression-oriented programming is awesome, and IO implementing common type-classes keeps you into the right paradigm. But “composition”, when used to justify the path we took (e.g., IO), is often just technobabble.

Algebraic reasoning #

What “algebraic reasoning” means is that math gets used.

But this spans multiple topics, so let’s see …

Design from first principles #

“First principles” are axioms, a word that I like more, used in the Romanian language as well — these are statements we consider to be true with no evidence (or implementation) available, or “intrinsic”, and then every other theorem or operation or principle gets derived from those statements. “Principled” simply means that the software system was started from a bunch of primitive/abstract operations and everything else was implemented in terms of those. Being principled is useful for demonstrating correctness. When adding new operations that get built on top of already available ones (e.g., non-abstract functions/methods), you don’t need to demonstrate again the correctness of your entire design.

Designing “from first principles” is a choice for the library authors in order to cut costs, and … that’s about all there is to it. As it does nothing for the user, and can be a hindrance as well. Because obviously, the real world isn’t principled. Even choosing the principles you’re building on is a matter of design (aka, ideology). There are really complex systems that you’re using every day, that aren’t based on first principles. Designs based on science and engineering are very often not based on first principles.

Type class laws #

Defining a “technology compatibility kit” (TCK) (aka “the laws”) … is important in case users can implement abstract interfaces / protocols that need a certain behavior that isn’t well expressed just via the exposed types. And these “laws” are defined with math language, with equivalence tests between expressions, but this isn’t a requirement for defining a TCK, and quite often math is not enough when testing the side effects.

When you see a flatMap, you know it should have a certain behavior (i.e., left+right identity, and associativity). Monad’s definition is described by “laws” expressed with math. And yet IO should not cache its result, a potential side effect that can’t really be described with math. Which is fine, I mean, the Reactive Streams specification + TCK isn’t algebraic, but it’s useful nonetheless.

I’d also argue that you don’t need algebraic properties in order to be able to operate things, to have a good mental model for it (that only has to be useful, not real). I keep recommending the book The Design of Everyday Things for that reason. Algebraic reasoning is useful in the design process, but if you have to look at math expressions in order to predict the behavior of the API you’re operating, that design is error-prone and hard to use.

People, programmers, in general, don’t care about algebraic reasoning. What people care about is the User Experience™️, and the harsh reality is that UX usually trumps theorem proofs. Just look at Go/Python versus Haskell. This is why statically typed languages aren’t winning the markets dominated by dynamically typed languages, and will never do, for as long as the UX doesn’t improve, as dynamic languages are great at UX.

Good UX is about exposing a user interface that, after some training, can allow the user to go in autopilot mode. Think about driving a car, as programming isn’t very different. In that sense, the laws of type classes can help due to having tests for common protocols, implemented by different types, such that you can rely on those protocols no matter what the types represent. I think the innovation is in having a TCK in the first place, and less about that TCK being algebraic.

Local reasoning #

“Local reasoning” means that:

- You can take a piece of code, and understand what it does, without the wider context in which it gets used;

- In the context of FP, it means that you can assess the correctness of a function call without depending on the history of its invocations (i.e., functions are deterministic);

For one, code makes sense locally, without a wider context. This isn’t a property of FP, necessarily. The Linux kernel is famous for rejecting C++ for that reason — C doesn’t have classes, and its subroutines need to have any state passed in as parameters. This makes it easier for code reviewers to judge commit diffs. Don’t believe me, see Linus Torvalds’ thoughts on C++:

For example, I personally don’t even write much code any more, and haven’t for years. I mainly merge…

One of the absolute worst features of C++ is how it makes a lot of things so context-dependent - which just means that when you look at the code, a local view simply seldom gives enough context to know what is going on.

That is a huge problem for communication. It immediately makes it much harder to describe things, because you have to give a much bigger context. It’s one big reason why I detest things like overloading - not only can you not grep for things, but it makes it much harder to see what a snippet of code really does.

Put another way: when you communicate in fragments (think “patches”), it’s always better to see “sctp_connect()” than to see just “connect()” where some unseen context is what makes the compiler know that it is in the sctp module.

And C is a largely context-free language. When you see a C expression, you know what it does. A function call does one thing, and one thing only - there will not be some subtle issue about “which version” of a function it calls.

So there are particular reasons why I think C is “as simple as possible, but no simpler” for the particular case of an OS kernel, or system programming in particular.

I think C is as far from functional programming as you can get. The language in which you pass stuff as void*, only to reinterpret it as anything, depending on context, is as mutable, as dirty and as unsafe as it can get. And here is Linus Torvalds, talking about being able to locally reason about its subroutines, better than he’d be able to do with C++.

Going back to FP, it’s nice when the correctness of a computation does not depend on the history of invocations. Eliminating non-determinism is the ideal in functional programming. The dirty secret, however, is that’s not happening with IO.

class Counter private (ref: AtomicInt) {

// Looks like it depends on the history of invocations to me 🤷♂️

// I mean, technically, the function call is deterministic, but it's

// not returning the data that we crave for, this being codata (computations);

def increment: IO[Int] = IO(ref.incrementAndGet)

}

The ideal in functional programming is for functions to return data, the output depending entirely on the call’s (explicit) input parameters, such that the output doesn’t depend on prior invocations of that function. But that’s when you avoid IO, because IO is modeling access to shared mutable state by definition.

You heard it here first, “local algebraic reasoning” is usually technobabble.

Is FP good at all? Is IO? #

Of course!

“Referential transparency”, driving the “substitution model” of evaluation, isn’t technobabble, although I have my doubts when we are talking of “codata” (suspended computations). But in fairness, with IO, even if the program is still modeling the access to shared mutable state, and still describes a step-by-step computation, fact of the matter is that IO keeps people honest.

For example:

- Access to heavy resources, that can only be built via side effects, has to be modelled via

IO; - This forces those resources to be passed as function or constructor parameters;

- Shared global state, even when it exists, becomes more local — ideally, still depends on code reviews;

- The state of the world (e.g., the current time, or randomness), passed as function parameters, forces saner data modelling (e.g., maybe you don’t need that timestamp there), and makes the code easier to test — ideally, or you can just have

IOeverywhere, much like having side effects everywhere;

All of these are best practices, but best practices are best enforced by a compiler 😈

Also, functional programming is expression-oriented programming, and expressions are awesome, as it puts you into the mindset of transforming data via pipelines (aka function composition). It’s all about the UX, frankly. It’s always about the UX.

I’m starting to have some doubts about using monads for modelling side effects, though, but I’m still digesting my feelings 🤷♂️