OOP vs Type Classes: Ideology

This article explores the difference between OOP design, and parametric polymorphism with Type Classes, as both are possible in Scala.

Motivation #

Scala is a hybrid OOP+FP language. If you love OOP, Scala is one of the best static OOP languages. But Scala also exposes parametric polymorphism and can encode type classes.

Thus, developers can also choose to use parametric polymorphism restricted by type classes (aka ad hoc polymorphism). As if choosing when to use immutability versus object identity wasn’t bad enough, developers are also faced with a difficult choice when expressing abstractions. Such choices create tension in teams, with the code style depending on the team leader or whoever does the code reviews.

Let’s go through what is OOP, what is ad hoc polymorphism via type classes, how to design type classes, go through the pros and cons, and establish guidelines for what to pick, depending on the use case.

Video Presentation (YouTube) #

I also gave a speech in 2021 at Scala Love in the City on this same topic. If you’re more into videos, rather than reading words, you can watch this as an alternative, although note this article series has more details that couldn’t fit in video form.

Head over to YouTube if you want to watch it:

Abstraction #

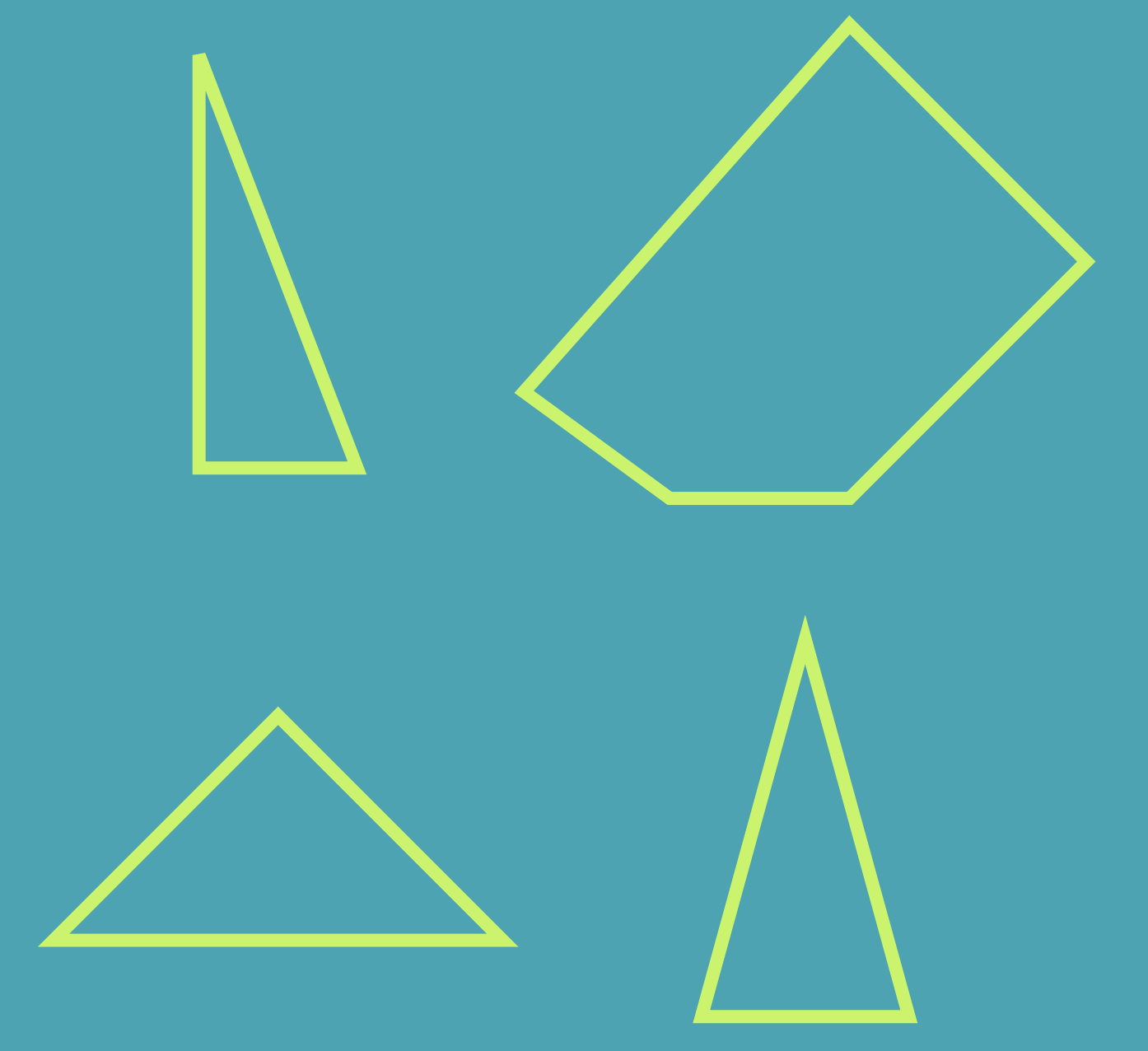

We are gifted with a brain that’s great at recognizing patterns. Take a look at these shapes, which one doesn’t belong?

What’s cool is that there is no right answer, you can point at any one of them, thus grouping the other 3 with some common characteristic. We have above:

- 3 triangles;

- 2 triangles with a right angle;

- 2 isosceles triangles;

- 3 shapes containing a right angle;

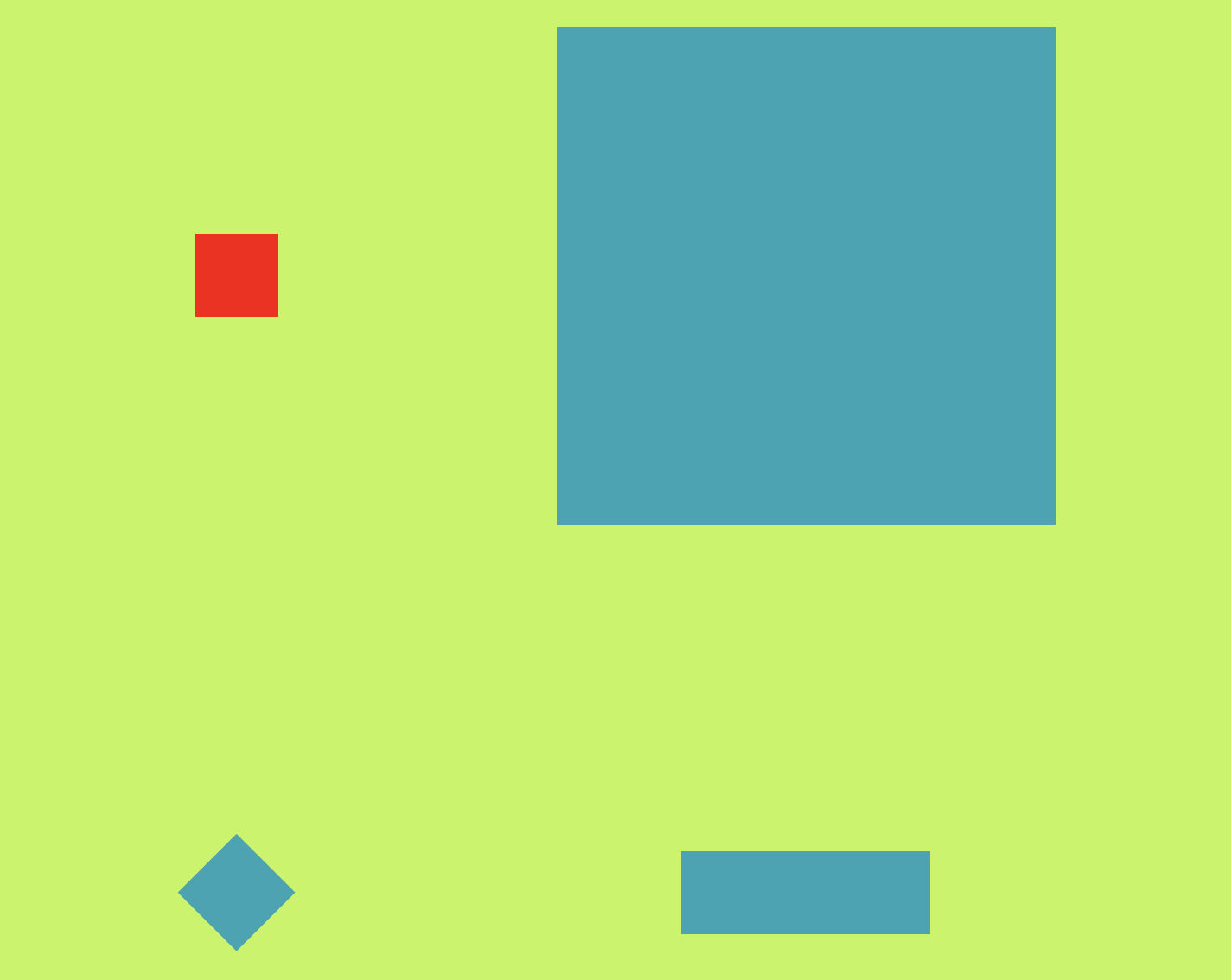

Here’s another one:

We have:

- 3 squares, and 1 regular quadrilateral that’s not a square;

- 1 red square, 3 blue;

- 1 big square, 3 small regular quadrilaterals;

- 1 square with a different orientation than the other 3;

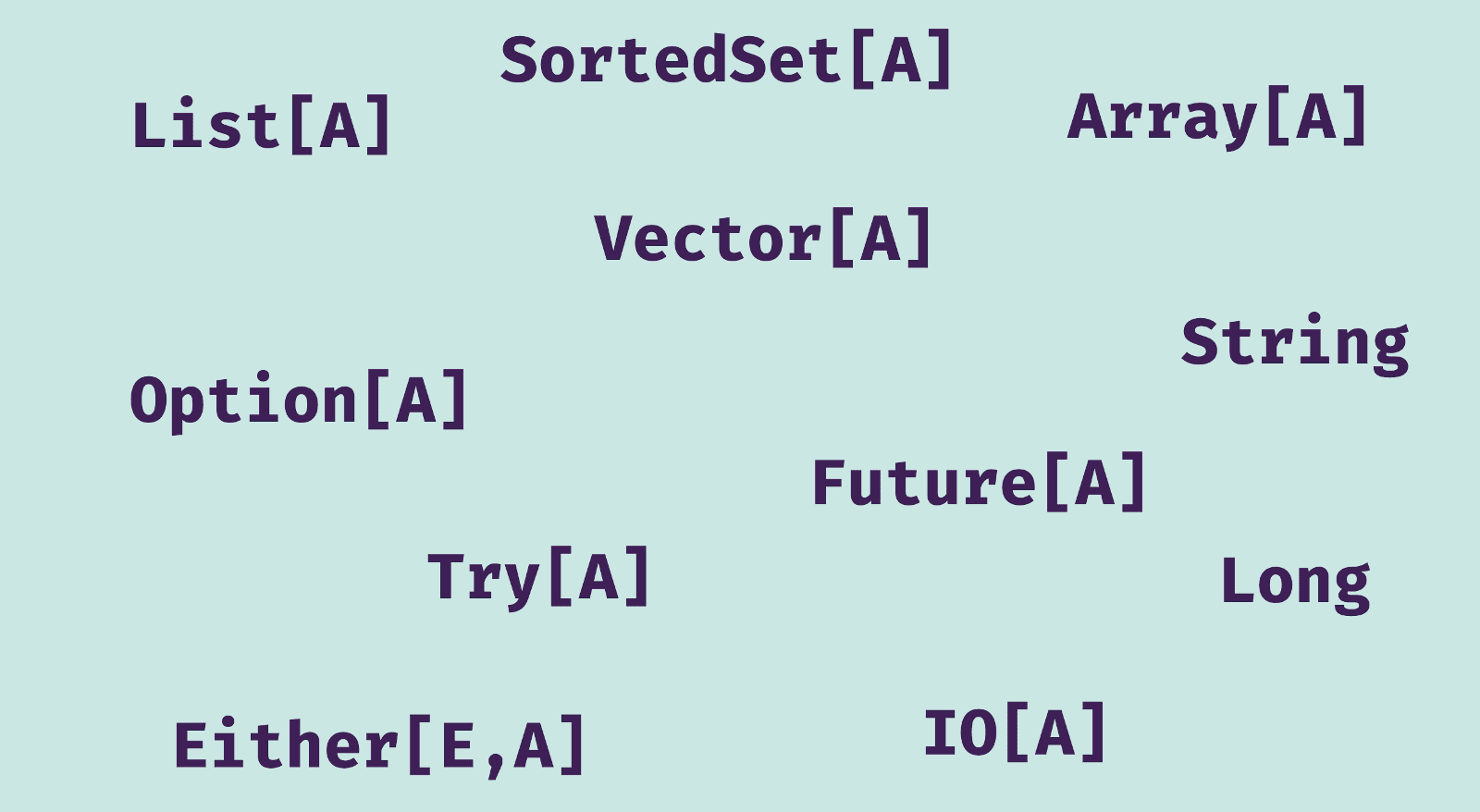

What about standard Scala types, how can you group these?

Some clues:

- Types that have a type parameter;

- Types that implement

mapandflatMap; - Types that implement

foreach; - Data collections;

- Collection types that can be indexed efficiently;

- Collections that have an insertion order;

- Types meant for signaling errors;

- Types for managing side effects;

- Types with a sum/concatenation operation;

- Types with an “empty” value;

We’re pretty good at observing similarities, right?

For these images, I’m plagiarizing Julie Moronuki’s The Unreasonable Effectiveness of Metaphor, a keynote and an article that I recommend.

So what is abstraction?

- “To draw away, withdraw, remove”, from the Latin “abstractus”;

- “To consider as a general object or idea without regard to matter”;

- “The act of focusing on one characteristic of an object rather than the object as a whole group of characteristics; the act of separating said qualities from the object or ideas” (late 16th century);

- “A member of an idealized subgroup when contemplated according to the abstracted quality which defines the subgroup”;

In the context of software development, abstraction can mean:

- idealization, removing details that aren’t relevant, working with idealized models that focus on what’s important;

- generalization, looking at what objects or systems have in common that’s of interest, such that we can transfer knowledge, recipes, proofs;

We do this in order to manage complexity because abstractions allow us to map the problem domain better, by focusing on the essential, and it also helps us to reuse code.

The complexity of software projects only grows over time and there’s only so much we can juggle with in our heads.

Black Box Abstraction #

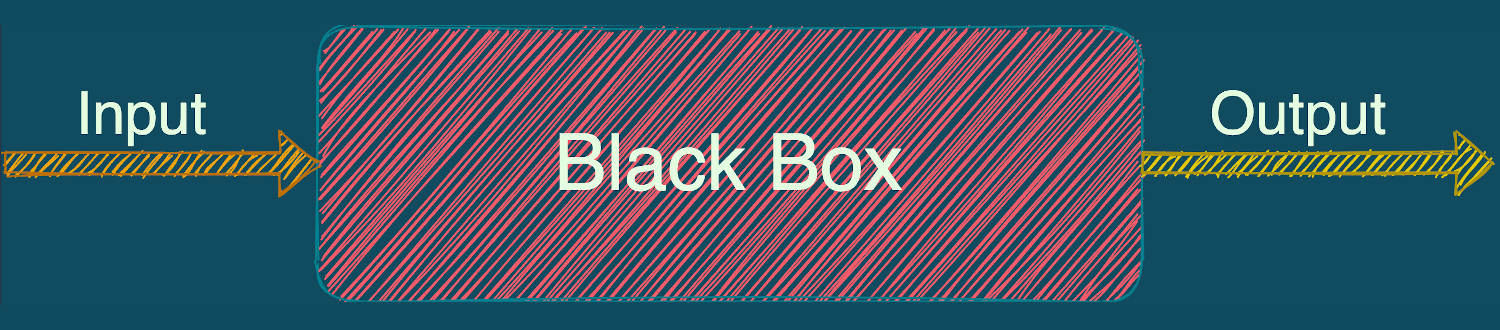

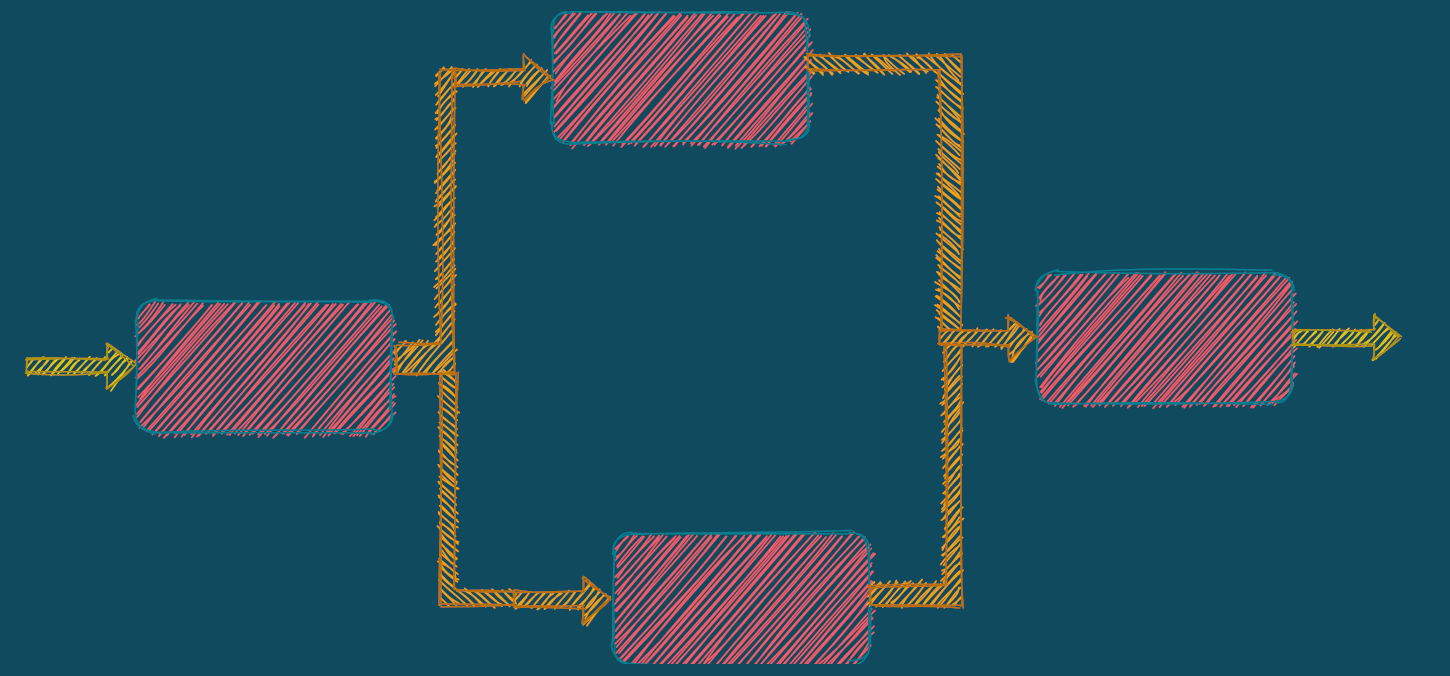

A black box is a device, system or object that can be viewed in terms of its inputs and outputs. This means that the input and output are well specified, such that we can form a useful mental model for how it works. Note that the mental model doesn’t have to be correct, it just has to be useful, such that we can operate the system without breaking it open and taking a look at the implementation:

These can be simple functions, associating one output value to one input, but not necessarily. Examples of complicated black boxes:

- Web services;

- Automobiles;

The input for an automobile is going to be the steering wheel, the gas and brake pedals. Automobiles are complex machines, but we don’t need to know how they work under the hood in order to drive a car from point A to point B.

And in software development, a common strategy is to build bigger and bigger systems out of black boxes:

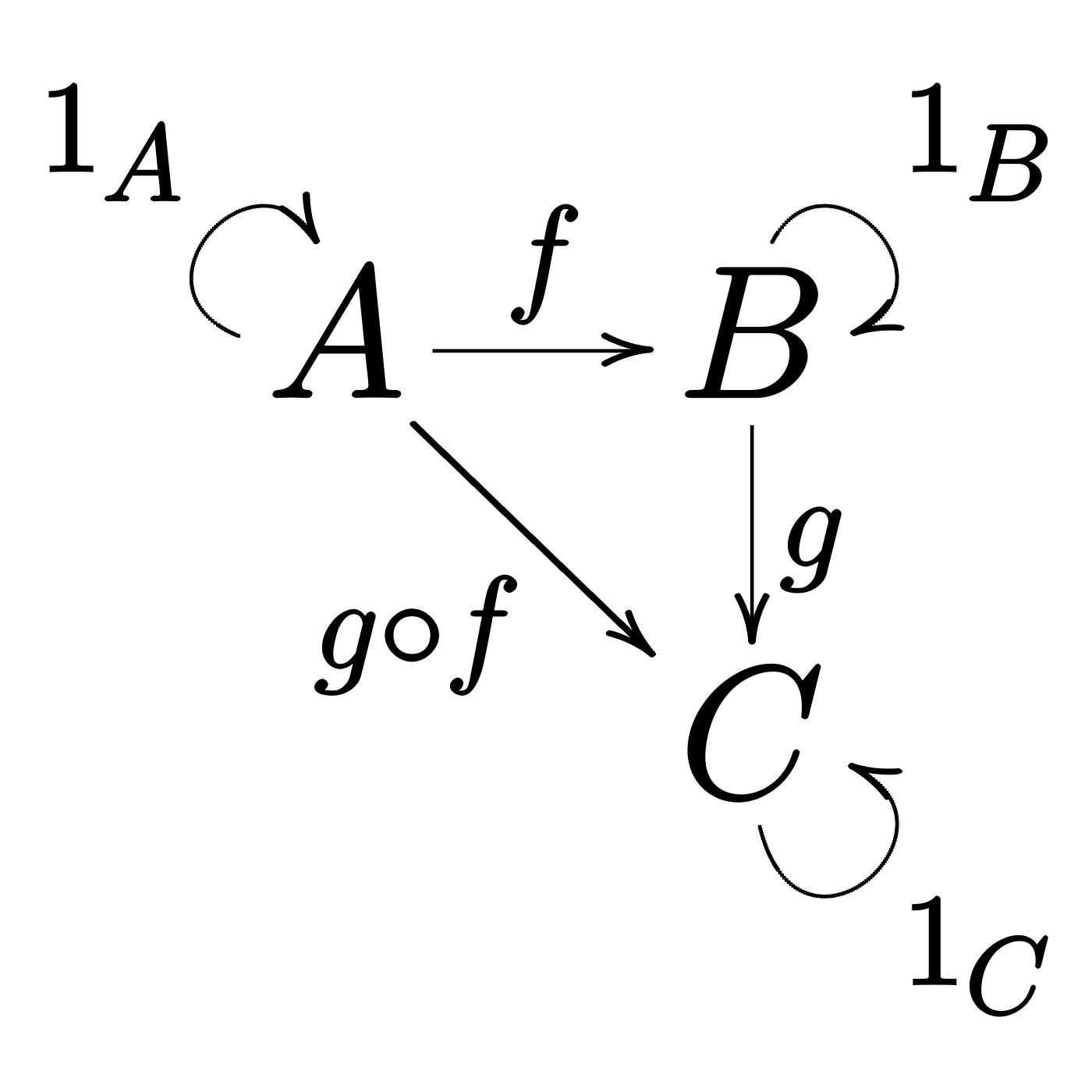

No paradigm has a monopoly on composition. FP developers can talk about functions composing, OOP developers can talk about objects composing. FP has the advantage that composition is more automatic, being governed by common protocols that have laws:

If f and g are functions, it’s easy to compose them in a bigger function, g ∘ f. Things get more complicated when the types involved don’t align. For example when that B type is a Future[_] or an IO[_]. But we can come up with protocols such that we can keep this automatic composition.

So what are we talking about?

- OOP-driven design is best for building black boxes, connected via design patterns for ensuring decoupling (the arrows between the boxes);

- FP-driven design is usually more about white-boxes; and for composing boxes, static FP gives us features such as Type Classes, for describing those design patterns via the type system, maximizing correctness and reusability;

🎤 drop — just kidding 😄

What is OOP? #

I like asking this question in interviews, as it’s a little confusing. Ask 10 people, and you’ll probably get 10 different answers, being a question that can be attacked on multiple axes: theory, philosophy, implementation details, best practices and design patterns.

OOP is a paradigm based on the concept of “objects” and their interactions, objects that contain both data and the code for manipulating that data, objects that communicate via messages. And in terms of provided features, we can talk of:

- Subtype polymorphism, via single (dynamic) dispatch;

- Encapsulation (hiding implementation details);

- Inheritance of classes or prototypes;

If there’s one defining feature that defines OOP, that’s subtype polymorphism, everything else flowing from it. Subtype polymorphism gives us the Liskov subtitution principle:

if S is a subtype of T, then objects of type T may be replaced with objects of type S

And note that OOP can be seen in the actor model; what are actors if not objects capable of async communication? And of course, web services behave like OOP objects, because OOP does a great job at modeling black boxes.

A great example of an OOP interface:

trait Iterable[+A] {

def iterator: Iterator[A]

}

trait Iterator[+A] {

def hasNext: Boolean

def next(): A

}

Implemented by most collection types. We’ll come back to it in a future article, to contrast and compare with a Type Class approach.

Are OOP and FP orthogonal? Can they mix? #

FP is about working with mathematical functions. Nothing stops objects from being “pure”, with their methods being math functions. For one, objects can perfectly describe immutable data structures, although these are less interesting, since they are just “product types” with names, or records:

case class Customer(

name: FullName,

emailAddress: EmailAddress,

pass: PasswordHash

)

When contrasted with FP, the notion of object identity (aka mutability) comes up a lot:

“FP removes one important dimension of complexity — To understand a program part (a function), you need no longer account for the possible executions that can lead to that program part” — Martin Odersky in Simple Functional Programming.

However, this is just an ideal, in practice being often a false statement. Let’s take a mutable interface:

trait Iterator[+A] {

def hasNext: Boolean

def next(): A

}

We can of course “purify” it via IO:

import cats.effect.IO

trait Iterator[+A] {

def hasNext: IO[Boolean]

def next: IO[A]

}

Is this not compatible with FP? How about this one?

final class Metrics(counter: AtomicLong) {

def touch(): Long = counter.incrementAndGet()

}

// FP version

final class Metrics private (ref: Ref[IO, Long]) {

def touch: IO[Long] = ???

}

What’s the difference between that, and this totally pure function?

object Metrics {

// Note the internals are now exposed, but function output

// depends entirely on function input FTW /s

def touch(ref: Ref[IO, Long]): IO[Long] = ???

}

Does that not have “identity” too? Of course, it does. Suspending side effects in IO is cool and useful, but in terms of divorcing a function from its context and history of invocations, that’s easier said than done, and FP won’t save you.

Classes are, after all, just closures with names.

In Scala almost every type definition is a class, and every value is an object, functions included. Interacting with objects happens only via method calls. Turtles all the way down. Scala's OOP facilities and type system are so powerful that they allow us to encode whatever we want, such as type classes or ML modules.

OOP may be orthogonal with FP, but the ideologies behind them are often at odds! So the answer to the question is: yes, they are orthogonal, but with caveats.

What are Type Classes? #

In static FP we have parametric polymorphism. Witness the simplest function possible:

def identity[A](a: A): A = a

// Compare and contrast with this one — how

// many implementations can this have?

def foo(a: String): String

This identity function can only have one implementation (unless you use reflection or other runtime tricks). But it would be useful to specify capabilities for that A type:

def sum[A](list: List[A]): A = ???

// Should work for integers

sum(List(1, 2, 3)) //= 6

// Should work for BigDecimal

sum(List(BigDecimal(1.5), BigDecimal(2.5))) //= 4.0

// Should work for strings

sum(List("Hello, ", "World")) //= Hello, World

// Should work for empty lists

sum(List.empty[Int]) //= 0

sum(List.empty[String]) //= ""

Can Scala’s or Java’s standard library provide this OOP interface?

First try:

trait Combine {

def combine(other: Combine): Combine

}

Yikes, that’s not good. We can’t combine any two objects inheriting from Combine. We can’t sum up an Int and a String, as this isn’t JavaScript 😊 Liskov’s substitution principle actually sucks here, as we care about the type, and we don’t want to lose type safety 🙂

trait Combine[Self] { self: Self =>

def combine(other: Self): Self

}

class String extends Combine[String] { ... }

def sum[A <: Combine[A]](list: List[A]): A = ???

We are making use of Scala’s self types, but as you can see, this barely works for combine, and we are missing an empty, the neutral element, “zero” for integers, or the empty string. Java/Scala OOP developers would give up at some point, and those stubborn enough would define this dictionary:

trait Combinable[A] {

def combine(x1: A, x2: A): A

def empty: A

}

def sum[A](list: List[A], fns: Combinable[A]): A =

list.foldLeft(fns.empty)(fns.combine)

Notice that Combinable is more or less the shape of that foldLeft operation.

These dictionaries are defined per type, and not per object instance. But wouldn’t it be cool if we also had automatic discovery? That’s what implicit parameters in Scala are for:

// Oops, the jig is up

trait Monoid[A] {

def combine(x1: A, x2: A): A

def empty: A

}

object Monoid {

// Visible globally.

// WARN: multiple monoids are possible for integers ;-)

implicit object intSumInstance extends Monoid[Int] {

def combine(x1: Int, x2: Int) = x1 + x2

def empty = 0

}

}

///...

def sum[A](list: List[A])(implicit m: Monoid[A]): A =

list.foldLeft(m.empty)(m.combine)

// Or with some syntactic sugar

def sum[A : Monoid](list: List[A]): A = ???

Behold Type Classes:

- Dictionaries of functions, defined per type, plus…

- A mechanism for the global discovery of defined instances, provided by the language.

Type-classes can have laws too. The Monoid here has the following laws:

combine(x, combine(y, z)) == combine(combine(x, y), z)combine(x, empty) == combine(empty, x) == x

These are like a TCK for testing the compatibility of implementations. Some type classes are lawless, because the laws are hard to specify, or because the signature says it all. That’s fine.

Let’s go back to this signature:

def sum[A : Monoid](list: List[A]): A

Can you see how it describes precisely what the function does? It takes a Monoid and List. What can it do with those, other than to sum up the list? There aren’t that many implementations possible.

With parametric polymorphism, coupled with Type Classes, the types dictate the implementation — and this intuition, that the signature describes precisely what the implementation does, is what static FP developers call “parametricity”

And as we shall see, this gives rise to one of the biggest ideological clashes in computer programming, being right up there with Vim vs Emacs, or tabs vs spaces 😎

Ideological clash #

OOP and FP are ideologies — sets of beliefs on how it’s best to build programs and manage the ever-growing complexity. This is much like the political ideologies, like the Left vs Right, Progressives vs Conservatives, Anarchism vs Statism, etc., different sets of beliefs for solving the same problem, promoted by social movements.

I’m not using this word lightly, computer science is not advanced as a science (via the scientific method), because computer science is also about communication and collaboration, therefore computer science also involves social problems, much like mathematics, but worse, because we can’t rely only on idealized models and logic. And investigating social issues via the scientific method is hard, therefore we basically rely a lot on philosophy, intuition, experience, and fashion.

Computer science is only self-correcting based on what fails or succeeds in the market, thus relying on free market competition. If a solution is popular, that means that it found product/market fit. The downside is that going against the tide is difficult, due to lack of credible scientific evidence. For example “it’s based on math” doesn’t cut it.

Two sides of the same metaphorical coin, both ideologies attack the problem of local reasoning and ever-growing complexity, and both have been succeeding, but from two slightly different perspectives.

We should learn from both, and we should have some fun while doing it, preferably without anyone getting hurt in the process.

OOP values #

- flexibility of implementation, meaning that the provider of an API only exposes what they can promise to support, leaving the door open for multiple implementations;

- backwards compatibility, think web services — if protocols often change, this is disruptive for teams having to do integration, new development often happens by feature accretion and not breakage, and in case of breakage, developers think of versioning, migrations and in-place updates of components such that disruption is minimal (on the downside, this also means web services exposing APIs with JSON documents having a lot of nullable fields 🤕);

- black boxes, components being described in terms of their inputs and outputs, data being coupled with the interpretation of that data (see this exchange between Alan Kay and Rich Hickey);

- resource management, in contrast with FP, which makes resource management the job of the runtime, in OOP languages like Scala we implement our own

IO, our ownHashMapandConcurrentQueue, etc., and that’s because we have good encapsulation capabilities, access to low-level platform intrinsics, and we don’t shy away from doing optimizations via all sorts of nasty side effects;

Static FP values #

I’m saying static FP because NOT ALL of these are values of the FP ideology as practiced in dynamic languages. I recommend watching Spec-ulation (YouTube), a keynote by Rich Hickey.

- flexibility at the call site, meaning that an implementation, like a function, should be able to work with as many types as possible, and this is often at odds with flexibility of the implementation, because it means restricting what the implementation can do via type signatures (a very subtle point, being a case of pick your poison);

- correctness, API signatures in static FP being very precise, correctness is awesome, but unfortunately this is at odds with backwards compatibility; correctness often means breakage in the API; static FP devs pride themselves with their language’s ability for refactoring, but refactoring often means breakage by definition;

- dumb data structures — based on the creed that data lives more than the functions operating on it, and that data structures can be more reusable when they are dumb, with interpretation being a matter of the functions operating on it, which can add or remove restrictions as they like; but this is often at odds with encapsulation and flexibility of implementation;

- OOP prefers black boxes, FP prefers white boxes;

- dealing with data — FP shines within the I/O boundaries set by the runtime (or by OOP), there’s nothing simpler than a function that manipulates immutable data structures, and such functions can be easily divorced from their underlying context;

- derivation of laws and implementations — static typing is about proving correctness, and static FP languages give us tools for automatically deriving proofs and implementations from available ones; e.g. if you have an

Ordering[Int]you can quickly derive anOrdering[List[Int]], which isn’t possible in classic OOP;

Degenerate cases #

Compare the degenerate signature for OOP classes:

trait Actor {

def send(message: Any): Unit

}

Versus the degenerate signature for parametric functions in static FP:

def identity[A](a: A): A

This is a spectrum of course. An Actor can implement literally anything, but dealing with it is very unsafe, that contract is useless, and all reasoning enabled by static typing goes out the window. And identity works for any type, maximally usable and composable, but it does absolutely nothing, in practice its utility being only to play “Type Tetris”, i.e. succeeding in the invocations of other functions by making the types match. It’s such a sad little function, in spite of being a star at FP conferences.

What do you want? #

These are the questions you have to ask yourself, and they are equivalent:

- Whom do you want to constrain, the provider or the client of an API?

- What do you prioritize, backwards compatibility or correctness?

What we want is everything, but we can only get some balance, depending on use-case. “It depends” is a boring answer, but the only correct one.

Everything I just said is the conflict of visions that also applies whenever we talk of the merits of dynamically typed versus statically typed languages 😎 It's a conflict of visions born from the problem domains and the compromises that people have had to make, which are then modeling their opinions. This conflict is always present, and people have to be aware of it when picking tools, techniques or languages, and when designing their programs, as these visions transcend the tools used or the programming languages and their features.

Coming up next… #

I hope you liked my 1st article on this topic, as more is coming. Watch this space 😎